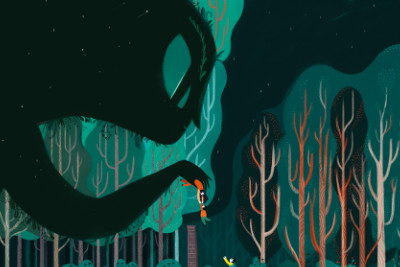

A Light In The Forest

- Raphaël Kolly

View in full on dPICTUS

Willkommen – bienvenue – benvenuto. Is it because of the

linguistic diversity that practically all Swiss children’s

book publishers focus on picturebooks? The reasons certainly

are more complex, but the real situation shows: Great

illustrations from a small country. Whoever lives here is

not always sure whether small is really beautiful. Everyone

knows almost everyone. How awful for young talents. Thus

many dream of success abroad. But the smallness is also

efficient: Colleges and support models enable high flights

of fancy without blocking the view of everyday life. The

results are excellent; take a look for yourself. Welcome to

the “Focus on: Switzerland” presentation on dPICTUS!

Hans ten Doornkaat

Editor, lecturer and critic

Pro Helvetia supports international publishers with contributions to the costs of translations and illustration license costs for works by recognised Swiss authors.

Discover the available grants and supportdPICTUS is part-funded by Pro Helvetia. This enables us to subsidise the showcase fees for Swiss publishers and agents, and more actively promote Swiss literature through our initiatives.

Fabrice Melquiot & Isabelle Pralong

Editions La Joie de lire

Peter Stamm & Hannes Binder

Atlantis Verlag

Reza Dalvand

Baobab Books

Caroline Stevan & Elīna Brasliņa

Helvetiq

Sylvie Neeman & Albertine

Editions La Joie de lire

Lisa Voisard

Helvetiq

Silvia Härri & Cristina Pieropan

Éditions Notari

Heinz Janisch & Aljoscha Blau

Atlantis Verlag

Hassan Zahreddine

Baobab Books

Germano Zullo & Albertine

Editions La Joie de lire

Lena Anlauf & Vitali Konstantinov

NordSüd Verlag

Tatia Nadareishvili

Baobab Books

Noémie Tagan & Elyn

Helvetiq

Catarina Sobral

Éditions Notari

Germano Zullo & Albertine

Editions La Joie de lire

Jasmin Schäfer

Atlantis Verlag

Andreas Greve & Lena Winkel

Atlantis Verlag

Reza Dalvand

Baobab Books

Valeria Aloise & Margot Tissot

Helvetiq

Regina Frey & Petra Rappo

Atlantis Verlag

Émilie Boré & Vincent

Editions La Joie de lire

The Bolo Klub is a long-term project that supports an emerging generation of picturebook artists in Switzerland.

The path is long and sometimes difficult between the first ideas at the origin of a project and its concretisation in a publication. This is why the Bolo Klub proposes several activities by organising exchanges between peers, meetings with more experienced authors and illustrators, as well as networking with publishers. The Bolo Klub enables the development of an engaged and self-supportive community for the making of high-quality picturebooks.

Every two years, the Bolo Klub invites to apply for the Bolo Klub Program, a program reserved for eight illustrators chosen by a jury. The Bolo members are accompanied over the course of a year by established illustrators and authors from throughout Switzerland that help them develop an illustrated book. Besides this mentorship, the Bolo Klub Program enables the Bolo members to exchange, provides networking opportunities with professionals from the publishing world, and sets deadlines for completing a book.

Johanna Schaible

Johanna Schaible, an artist and illustrator from Bern, submitted her project to the first dPICTUS Unpublished Picturebook Showcase. Johanna’s project Once upon a time there was and will be so much more was independently voted for by 23 of the 30 publishers on the jury, and has since generated a lot of excitement and interest. The book was published in 2021 by Lilla Piratförlaget from Sweden, as a co-edition with nine international publishers. Lilla Piratförlaget publisher Erik Titusson says: “When turning over the continuously changing pages of this book, you physically feel the passing of time. This is a truly unique project and a moving experience for readers of all ages. The theme of the book and its innovative design work hand in hand to reinforce the feeling that here we are in the world, right now, at this instant, and from this point on: we build the future!”

Read a review of the book by Mac Barnett in The New York Times

Johanna talking about the project on the Picturebook Makers blog

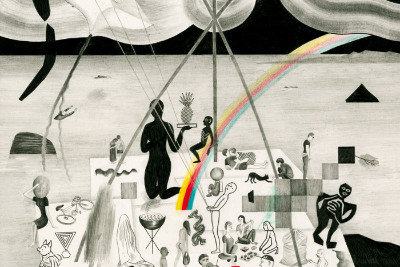

Germano Zullo studied economics before becoming a prolific author. Albertine’s illustration career began after graduating from art school in Geneva. The couple marrried in 1996 and have since collaborated on many books and won awards such as a Biennial of Illustration Bratislava Golden Apple and a BolognaRagazzi.

See this post from Germano Zullo & Albertine >Nina Wehrle and Evelyne Laube, known as It’s Raining Elephants, create books, illustrations for diverse applications and their own ceramics line called HOI. Nina and Evelyne have won numerous awards including the Fundación SM International Award for Illustration at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair.

See this post from It’s Raining Elephants >Johanna Schaible is an artist whose work moves along the borders of illustration, art, and design. She was one of the first members of the Bolo Klub, and her debut picturebook ‘Once upon a time there was and will be so much more’ has been published in many languages and has been recognised in several prestigious awards.

See this post from Johanna Schaible >Daniel Fehr is a picturebook author and board game designer. He studied photography at Zurich University of the Arts and the School of Visual Arts in New York, and then he studied German literature and media at Princeton University. Daniel currently lives and works in Winterthur, Switzerland, the town where he grew up.

See this post from Daniel Fehr >Francesca Sanna grew up in Sardinia. She first moved to Germany and then to Switzerland where she achieved a Masters of Art in Illustration at the Academy of Art and Design in Lucerne. In 2017, she was awarded the second Klaus Flugge Prize for the most promising and exciting newcomer to children’s book illustration.

See this post from Francesca Sanna >Anete Melece studied Visual Communication at the Art Academy of Latvia and Animation at Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts. Her animated short ‘The Kiosk’ has been shown in film festivals around the world and received many awards. Anete lives and works in Zürich as an animator and illustrator.

See this post from Anete Melece >

Atlantis Verlag has been publishing children’s books for more than 80 years. With their high-quality pictures and texts, these books for preschool children are an invitation to read aloud and to contemplate. Atlantis picturebooks make their mark through both content and graphics, while emphasising a diversity of styles. Books on themes of daily life are featured, as are sophisticated and artful picturebooks for connoisseurs. Since 2003 the Atlantis Verlag has been part of the Orell Füssli Verlag, of which it is an imprint.

A picturebook from Iran, a myth from the Maya culture, a young readers’ novel from Japan... Sometimes in two languages, sometimes even handmade: the Baobab Books programme is unique. For more than 25 years, the press has published German translations of children’s and young readers’ books from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania, as well as from the more remote regions of Europe. A special focus is placed on indigenous peoples.

Founded in 1987 by Francine Bouchet, La Joie de lire publishes high-quality children’s and young readers’ literature distinguished by original and meticulous illustrations. About 45 new titles are published every year – the catalogue includes some 700 – and they are proud of the fact that their books continually speak to the spirit of the times.

Éditions Notari was founded in 2006 by Luca and Paola Notari. The Geneva-based press publishes art and young readers’ books; the latter are characterised in equal measure by high quality in artistry and content. All books are in French. The press publishes both original works and translations.

The Helvetiq story began in 2008 with a game about Switzerland. Since then, this international press, with headquarters in Basel and Lausanne, has been creating new books and games. Its goal is to put out whimsical books that inspire, that incite people to laughter and that reveal the unfamiliar in the familiar. The press focuses on leisure products and children’s books.

NordSüd Verlag is a tradition-steeped children’s book publisher based in Zurich. Together with the imprint NorthSouth Books in the USA, the press is internationally prominent, publishing around 60 new publications every year. The discerning programme for children features texts and illustrations from around the world. The best-known NordSüd publications include The Rainbow Fish by Marcus Pfister and Edison by Torben Kuhlmann.

Hans ten Doornkaat

Editor, lecturer and critic

Switzerland not only has four official languages; its linguistic complexity goes far deeper, even just within the German-speaking part. When a child learns to read and write there, she has to take an extra step, moving from the dialect spoken in everyday family life to so-called Standard German. This juxtaposition of spoken and written language is experienced by children in many countries. However, because the standard language for German-speaking Swiss is not merely the language of a social class, but is closely linked in the general perception to a different country, the discrepancies are more apparent. This conscious switching between spoken and written language is probably among the reasons that well-known German-language Swiss authors for children – like Franz Hohler, Jürg Schubiger, Hans Manz and Max Huwyler – use puns and other wordplay strikingly often. This phenomenon can also be seen in adult poetry, from Eugen Gomringer to Kurt Marti, and also in chansons, poetry slams and spoken word.

Should one suppose that illustration carries a special weight in places where learning to read involves overcoming particular hurdles? That would be a daring proposition – but ultimately not a convincing one. Since the turn of the century German-speaking Switzerland has indeed produced significantly more picture books than books for young adults, but that is another story. A small country (especially one that is culturally diverse within its own borders) more naturally keeps an eye on what larger countries are doing. When, in the 1970s, a new interest in literature from other continents emerged in Western Europe, not only did Swiss publishers like Lenos and Unionsverlag release important works of fiction, groups engaged in the politics of development also examined the new children’s books available in German, and assessed them according to their content and literary value. Out of these working groups came Baobab Books, a publishing house that promotes intercultural reading skills and initiates international projects.

The SJW press, which focuses “inwardly”, is nevertheless dedicated to linguistic diversity; it publishes the booklets of the Schweizerisches Jugendschriften Werk (Swiss Youth Writing Editions) foundation in four languages. The SJW had its origins in the campaign against trite and trashy literature in the interwar period and was dedicated to publishing inexpensive “good” literature – exclusively by Swiss authors – to be sold directly in schools. Since 2006 this reactionary system has been transformed into an innovative platform – it is still focused on Switzerland, but aims to challenge aesthetic boundaries. Thus the SJW published the first work of the artistic duo It’s Raining Elephants, The Big Flood (2011), a folder with posters and accompanying texts that has earned international recognition at the highest levels.

The next book by It’s Raining Elephants, featuring provocative questions and associative images relating to the legend of William Tell, was published by the Spanish press SM Ediciones (in a series that features winners of the Bologna Ragazzi Award at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair). That the artists took up the topic suggested by the Spanish publisher – and that the rights so far haven’t been bought by Swiss publishers – is consistent with the great arc of history: the most famous adaptation of Tell was written by Friedrich Schiller, an exponent of German classicism. (1) In Switzerland, the famous apple shot appears in illustrated form largely in popular publications, such as those involving Globi, the most successful German-speaking Swiss cartoon character. Critical discussions of Tell – by authors such as Max Frisch and Jürg Schubiger – have only appeared in non-illustrated form.

The most important Swiss contribution to international children’s and young adult’s media is still Heidi, followed by A Bell for Ursli. Heidi stems from the sentimental narrative form of the 19th century, and from the very start has served to promulgate the myth of the Alps, which has itself long been an effective promoter of tourism. Ursli, the mountain boy from Graubünden who struggles against all odds to get the largest cowbell for the children’s parade, exemplifies an important kind of self-assertion. As an object of identification, on the one hand he matches developments in 20th century children’s literature, in which – and not only in books by Erich Kästner and Astrid Lindgren – children prove themselves by challenging prohibitions laid down by adults. On the other hand, the little boy from the mountains incarnates ideas of national identity from the period before and during the Second World War.

Publishing houses and the promotion of reading experienced an awakening after the war, joining together in a pioneering spirit. International organisations were needed to give form to the idea of a “children’s book bridge” as a means of promoting international understanding, and it was not by chance that relatively neutral Switzerland became a favoured meeting place. In 1953 the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) was founded in Zurich; today it is headquartered in Basel.

But Switzerland after 1945 also had a lot to offer in the area of children’s literature itself, especially in the realm of the picture book. For Alois Carigiet, Felix Hoffmann and Hans Fischer, the isolation of the war years had also meant a protective space. In addition, Swiss poster art was highly developed, and had forged many links with the world of picture books before the discipline of graphic arts split off from that of illustration; internationally known in this context are Herbert Leupin and Celestino Piatti.

Children’s book presses in German-speaking Switzerland were thus at the vanguard of international developments in the 1950s – including in the acquisition of rights. In the 1960s the publisher Diogenes became a hotspot for illustrated books. Tomi Ungerer and Maurice Sendak found in Daniel Keel a publisher like no other to bolster the positioning of their works between the genres of children’s and art books. Swiss publishing houses were in general well prepared when, in the years following 1964, an international children’s book fair in the tradition-steeped mercantile city of Bologna became a quickly growing hub for children’s literature. In addition, Switzerland profited from the initiatives of Eastern European immigrants:

• In 1960 Dimitrije Sidjanski and his wife Brigitte Hanhart founded NordSüd. At first the publishing house was based in the family’s home; when the catalogue was successful, thanks to both Swiss and foreign artists, the press moved to Gossau-Zurich, where the international stars Hans de Beer and Marcus Pfister provided further impetus for its expansion.

• In 1973 the Czech exiles Otakar Božejovský and Štěpán Zavřel dared to found another press, which they might have called the Ost-West Verlag; instead they chose to emphasise its Bohemian roots. Max Bolliger, Eveline Hasler and Regine Schindler, all authors of important children’s books, showed up at the Bohem Press with ideas for picture books. Swiss texts with foreign illustrations proved to be a model for international success.

When mergers flooded the bookselling and publishing businesses at the turn of the millennium, a countermovement began: the publishing catalogues of Sauerländer, Nagel & Kimche, Bohem and Bajazzo were bought up by German publishers, as was NordSüd, though its headquarters remained in Zurich. That in the last few years new publishers have been founded (e.g., Aracari), and children’s book programmes expanded (Baeschlin), this only demonstrates that every trend gives rise to a countertrend. Hadi Barkat’s recently founded Helvetiq is another case in point; Barkat grew up speaking Arabic and French in Algeria and thinks in terms of crossing all kinds of frontiers, including that between books and games.

Publishing has always influenced illustrations, even before the twentieth century. Ernst Kreidolf, a forefather of European picture book art, emigrated to Munich in order to study painting. There he influenced the development of Jugendstil illustration before returning to Switzerland – among other reasons because he had found a publisher whom he trusted.

One could maintain that there is no specifically Swiss style of illustration, not only because of Switzerland’s diverse linguistic cultures, which tend to look abroad, and the global trade in rights, but especially because Swiss cultural exchange was always more international than a focus just on Switzerland would allow one to appreciate. And anyone who uses the internet today as a treasure trove of styles and motifs illustrates with a different scale of orientation anyway. Moreover, formal trends, like ever shorter texts in picture books, are even more influential. And the power of branded characters and international content forces some publishers to operate on a different scale entirely. And yet, there is something Swiss in Swiss illustration.

Whoever is thinking at this point of snow-covered mountains, steamships on every lake, railroad viaducts, picture-perfect houses and cows with bells hanging from their necks, confirms that the logo of the Swiss presence as Guest of Honour is fitting. Such iconic images represent the standard motifs of the country. (2) Swiss react ambivalently to this; the rest of the world, predominantly positively. Peter Bichsel, today’s doyen of Swiss literature, cut to the chase as a young author: “We have gotten used to seeing Switzerland with the eyes of our tourists. (…) Our picture of our own country is a foreign product.” This assessment from 1967 still hits the mark a good fifty years after it was made. (3)

What do I think of, then, when I think of what is particularly Swiss in contemporary picture books? I now consciously (and fittingly, given the emotional resonance) switch into a subjective mode, though I will back up my assertions – objectively – with examples of books: when in 2016, Atlantis, NordSüd and SJW all came out with new books about the construction project of the century, the Gotthard Base Tunnel, the national context was evident. When Claudia de Weck illustrates narrative non-fiction picture books that address day-to-day topics like the dangers of poison or the meaning of money, she is illustrating texts that Lorenz Pauli has written on assignment from a foundation or a federal agency. Yet in the background, though hardly noticeable, there is not a single piece of furniture that couldn’t be found in Switzerland. Kathrin Schärer’s story Pippilothek (The Fox in the Library) has had rights sold in sixteen countries. Only Swiss children, however, will recognise in the scenery of the fable the same bookshelves that they know so well from their local libraries – a piece of their daily life. Even if nobody consciously picks up on this, the signals sent by these images are more than just evidence for the authenticity of the illustrations. They represent an enormously important potential of books as “small” productions – while Netflix and Disney, blockbusters and games, due to the sheer size of their operations, favour uniformity and standardisation.

Even more relevant than Kathrin Schärer’s bookcases is the setting in Vera Eggermann’s telling of Alois. Her boisterous young bull doesn’t live on a farm in the mountains, but in a pasture at the edge of a city. “Modern” children climb the fence, and a wealth of details locate the timeless fable in the Swiss here-and-now. Hannes Binder works to the same effect. When the water drains away in his The Second Ark, the ship comes to rest in the middle of a city. Though the text composed by the Austrian writer Heinz Janisch has an archaic flavour, the pictures show the contemporary Zurich of the illustrator. What’s happening here is not folklore, then, but a conscious mirroring of what is known and trusted. (4) In this sense, picture books represent a guerrilla medium against the stew of international conformity. Quite often just such illustrations, because they are more complex, awaken worldwide interest. And no wonder: illustration is not art for art’s sake. Illustration is communication, ideally in a language that differentiates. It thus needs a base in life, a home – no less when chasing after the fantastical. Even when illustrators narrate incredible stories, the act of looking carefully renders their drawings more human.

I can’t rule out that such traces are also present in illustrations from other countries. I couldn’t identify them all – but I do wish it for them, because what is looked at makes illustrations more interesting than what is merely thought out. Art lives in the details.

© 2019 SBVV Swiss Booksellers and Publishers Association, All rights reserved.

Letizia Bolzani

Editor of the magazine Il Folletto,

published by the Istituto svizzero Media e Ragazzi ISMR

To sketch the history of children’s book illustration in Italian-speaking Switzerland, we would have to begin with the oldest children’s book publisher, the Edizioni Svizzere per la Gioventù (ESG), which has been publishing its excellent little books (soberly called “booklets”) for almost a century and directing them – in large numbers – at Swiss schoolchildren. Looking at its first publications for Italian-speaking Switzerland, which appeared during the 1940s, we find all the great painters who made Ticino famous as a land of artists: Luigi Taddei, Felice Filippini, Filippo Boldini and Carlo Cotti, to name just a few. They were, however, painters; these were not yet illustrators, with that consciousness of the specificity of their expressive language, in particular in engagement with texts, that had by that time already made its mark in the rest of Europe.

Browsing through the archives of the ESG, it is only when we arrive at the 1960s that we find the first artists who also began to express themselves as illustrators. This turning point coincides with the founding of the CSIA (Centro Scolastico Industrie Artistiche) in Lugano, established at the suggestion of Pietro Salati in 1961 in response to a changing world that saw a rising demand for designers in industry, including publishing. And in fact, among the illustrators for the ESG at that time, we find a new generation of Ticinese artists who were also teachers – such as Emilio Rissone, Nag Arnoldi and Lulo Tognola, and various other famous painters.

It is also of great significance that publishing for children in the Italian-speaking world has become ever richer and more diverse, awakening the interest of new talents, who in the last twenty years have focussed more and more on creating children’s books. During this time, female names finally appeared in the field of illustration, and in substantial numbers: at first the trailblazer Fiorenza Casanova, and then also younger illustrators who, having published various titles abroad, are already well-established today – such as the Graubünden native Ursula Bucher, Simona Meisser from Lugano, and the Locarno native Valérie Losa (who works in French-speaking Switzerland). We should also mention Sara Guerra, who was selected to represent Switzerland at the 2018 Bologna Children’s Book Fair, as well as, of course, Paloma Canonica, who works in Spain today, and is featured in this year’s exhibition, “A Swiss ABC”. Among their male colleagues we should mention Micha Dolcol, who comes from the Ticinese village Tremona, and especially the prominent Frenchman (but resident in Ticino) Antoine Déprez, also known for his international publications. As a crossroads of different cultures and places of origin that mirrors on a small scale the multiculturalism typical of the whole country, Italian-speaking Switzerland represents an artistic region whose illustrative productions are diverse, growing and very lively.

© 2019 SBVV Swiss Booksellers and Publishers Association, All rights reserved.

Katia Furter

Librarian with a focus on children’s

and young adult’s literature

Since Switzerland consists of four language regions, each of these quite naturally turns to the culture of its nearest neighbour, feels close to it and incorporates it. In French-speaking Switzerland the majority of our reading material comes from France, whose illustrative art speaks to us more than does that of German-speaking Switzerland. For that matter, picture books seldom make the move from one Swiss language region to another, and our knowledge of the artists who produce them is fragmentary – although bridges are certainly being built and there is a lot of admiration expressed. (1)

In the spirit of the Genevan Rodolphe Töpffer (1799– 1846) – the inventor of comic strips and possibly the first comics artist in history – there is an innovative and often even pioneering aspect to the art of illustration in French-speaking Switzerland. In 1951, the first picture book in the series Histoires d’Amadou (Stories about Amadou) was published, the conception of Alexis Peiry and the photographer Suzi Pilet. At that time, during which pedagogical and religious circles still kept a vigilant eye on children’s books, Pilet’s talent for experimentation and staging dreamlike scenes revealed possibilities of breaking out of conventional forms and provided a welcome breath of fresh air.

In the late 1960s Etienne Delessert became well known, first in the United States and later in France. His unmistakable manner of drawing fit perfectly into that epoch, in which children’s books were exploring new territory and were underpinned by the high artistic quality of their illustrations. Delessert founded the animation studio Carabosse in Lausanne, and then, in 1977, the publisher Tournesol. Monique Félix, who would later illustrate Histoire d’une petite souris qui était enfermée dans un livre (The Story of a Little Mouse Who Was Locked Up in a Book) also worked at this press. Children subscribed to the French-language Swiss magazines Mon Ami Pierrot (My Friend Pierrot) and Le Crapaud à lunettes (The Toad with Glasses), in the latter of which the first episode of Derib’scomic Yakari appeared. The first episodes of Cosey’s Jonathan, on the other hand, appeared in the Belgian magazine Tintin. Then came the bountiful 1980s, during which Etienne Delessert developed his character Yok Yok in all its his many facets. The Association romande de littérature pour l’enfance et la jeunesse (2) (AROLE – Romand Association of Literature for Children and Young People) campaigned for high-quality literature in its magazine Parole. It foregrounded outstandingfemale illustrators from French-speaking Switzerland, many of whom were represented in the association, and to whom we should add Béatrice Poncelet – what a shock the discovery of Je pars à la guerre, je serai là pour le goûter (I’m Heading off to War, I’ll Be Back for a Snack) was – and Anne Wilsdorf – who hasn’t read M’Toto? Then in 1987 Francine Bouchet founded La Joie de lire, a publishing house whose catalogue features top-class Swiss and French literature for young people. Finally, in the early 1990s, onto the stage stepped a strange character who unsettled librarians but delighted children: Zep’s Titeuf. Illustration in French-speaking Switzerland became enriched with new names and new genres, from illustrated picture books to cartoons (3) to comics.

Thanks to the talents of its authors and the quality of its publishing houses, French-speaking Switzerland plays in the premier league of children’s book publishing. Its limited size – and thus its sensitivity – compels it to extraordinary accomplishments in order to be successful beyond its borders, and to expand its market. Its illustrators also live and publish in foreign countries, especially France and Belgium. Those among them who have studied art often did this outside of Switzerland, because Swiss art schools ignored illustration as an art form for a long time. Is this perhaps the reason that it is difficult to speak of a particular style that is characteristic of French-speaking Switzerland, and why regional, folkloric topics are seldom taken on – except when Fanny Dreyer, in her Brussels studio, draws a traditional procession up to the alp, or when the Frenchwoman (!) Jacqueline Delaunay creates a book about Herens cows for La Joie de lire? Considering that Swiss art schools (4) are now offering courses of study in illustration and have an international outlook, it will be interesting to observe how things develop in this respect. At the moment – as has always been the case – there is a unique and sometimes pioneering spirit to our illustrators: the absence of a communal “school” drives some to boldness and others to experimentation. If they have anything in common, it is the quality of their work. In the world of French-speaking Swiss publishing, there are practically no poor-quality illustrations.

© 2019 SBVV Swiss Booksellers and Publishers Association, All rights reserved.